“Pick yourself up by your bootstraps”

The wisdom and folly of giving something for nothing

Imagine a man who has never had a job. He has never even applied for a job. He has never offered to be useful in exchange for cash, such as washing someone’s car or wiping down their windows. He has never taken the initiative to collect cans and bottles for the deposit. He has never done anything that could be considered useful for society. All he does is stand, or sit, by a busy intersection, and hold his hand out for cash. Cash for which, presumably, other people have exchanged bits and pieces of their life. If given the opportunity, would you hand this person a dollar? If you travel the same way every day, would you give him a dollar every single day? $365 per year? How many hours did you have to spend, away from your friends, family, and home, producing something of value, in order to earn $365 for this man who produces nothing but waste?

And what precedent is being set by your $1 per day donation? If 100 people are giving him $1 per day, don’t you think there are others who would see this as an opportunity? That standing on a corner for $36k per year, plus whatever benefits the city and state provide (also on the dime of the productive), is a far better option than stocking shelves for half the money? Aren’t we, in fact, failing the very people we are purporting to help by incentivizing indignity, entitlement, and listlessness? How much of that money is he going to spend on drugs, anyway? Why don’t we offer him a job instead? Why doesn’t he lift himself up by his bootstraps?

My liberal readers will know how to answer the “bootstrap” question. Some people were born with shorter bootstraps than others; some people don’t even have boots; hell, some people don’t even have feet! We have a duty as a society to help those less fortunate, particularly those whom society has failed.

It has always struck me that both of these perspectives are correct. There are people who will never be able to hold a job, or contribute to society, through no fault of their own; there are also people who will take advantage of the people and systems put in place to care for the genuinely disadvantaged. Pragmatically, as an individual, you’ll almost never have enough information about an individual to know whether or not they are worthy of your donation. The best that we can do from a policy perspective is to build structures that enable us to maximize the care for those who cannot care for themselves, while at the same time, minimize the ability for the free-loaders who are able to care for themselves, but choose not to. It’s impossible to do perfectly, and there are always going to be some people who suffer who could have otherwise been helped, and some people who grift.

Grading and attendance policies in school run parallel to the challenges in the above scenario. Really, the two challenges: the problem with the problems, and the problem with the solutions.

About two weeks ago, my colleague and fellow English teacher Loren Green spoke directly and publicly to the school board about his concerns regarding student grading and attendance policy in the City School District of Albany. The Times Union and Fox News picked up the story, and there has been some talk of organizing a teacher-led letter or speaking campaign to further explain and emphasize Loren’s main points. His basic argument was that the school does not have a grading or an attendance policy. Students will pass regardless of whether or not they hand in a single assignment, or regardless of whether or not they attend a single class, and if the teacher dares to fail them on the basis of their doing nothing, then a school administrator will reach into the gradebook and force a grade change. Loren has claimed (and I know this to be true) that the school principal has done exactly this to him last year - that he failed students who did not meet his minimum and reasonable expectations, and she chose to change the grades to passing. He also claims that there is pressure, both implicit and explicit, to pass students who have not met the minimum requirements for passing.

There are more “inside baseball” details to this story. For example, as I understand it, the school principal does have the contractual right to make such adjustments, at her discretion. There is pressure to pass students, although in my experience it has been more implicit than explicit. I know of at least one untenured teacher who claimed she was let go due to failing too many 9th graders, and I found her claim credible (although, to be fair, others haven’t). Let’s put these messy details to the side for a moment and explore a different question:

How is giving money to a man who did not earn the money, the same type of thing as giving points to a student who did not earn the points?

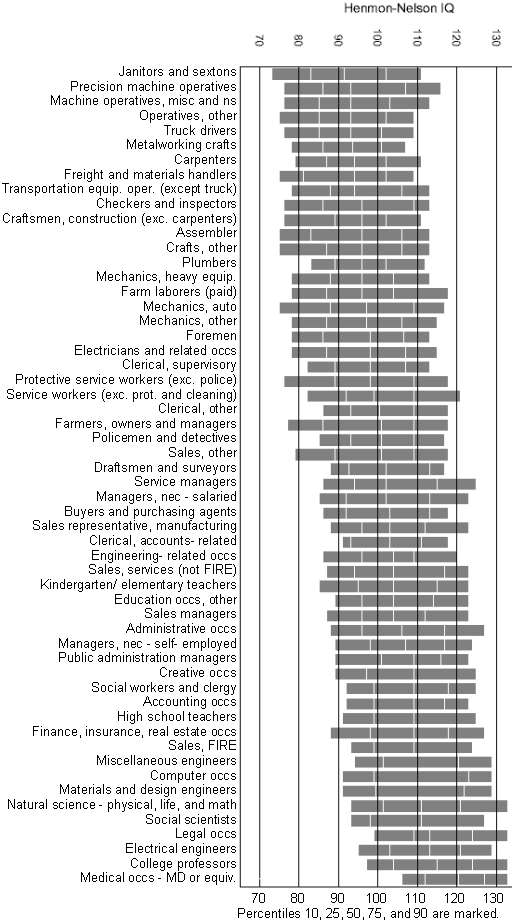

The typical liberal claim, and one that I’m sympathetic to, is that some people cannot support themselves economically (cannot pull themselves up by their bootstraps) because they are in some way incapable of doing so. But why would it be impossible for some people to support themselves? Any number of reasons, but we could start with IQ. According to the chart below, anyone with an IQ of 80 or lower is going to have a tough time finding and maintaining employment, and anyone with an IQ of lower than 70 is going to be virtually unemployable. In America, almost 19 million adults have an IQ of 80 or lower, with about 10 million of those being at-or-below 75. That’s a minimum of 10 million people who won’t be able to hold a job even if they wanted to, if we considered IQ and IQ alone (and there are other reasons why one might not be able to hold a job).

High school curriculum, at least in theory, is far more advanced than most jobs that a person with an 80 IQ could manage. In NY, 22.5 credits are required to graduate, including five “Regents” exams in world history, US history, math, English, and science. There are 25 million children ages 12-17 in the United States, which means approximately 2.25 million have an IQ equal to or less than 80, of which 1.2 million are equal to or less than an IQ of 75. The liberal version of “bootstraps” is “apply yourself” or “try harder” (grit comes to mind). Someone with an IQ of 75 is not going to be successful in algebra, and it has nothing to do with bootstraps, effort, grit, or even the actual grade that winds up on their report card. It’s just not going to happen. The argument I would make is that such a student does not belong in an algebra class at all; however, in NY it’s a requirement for graduation, so they have to take the class. Giving a student with an IQ of 70 “only the points they earn, and only once they master the material” feels an awful lot like telling the homeless man to “get a job!” Well…yeah, if they could.

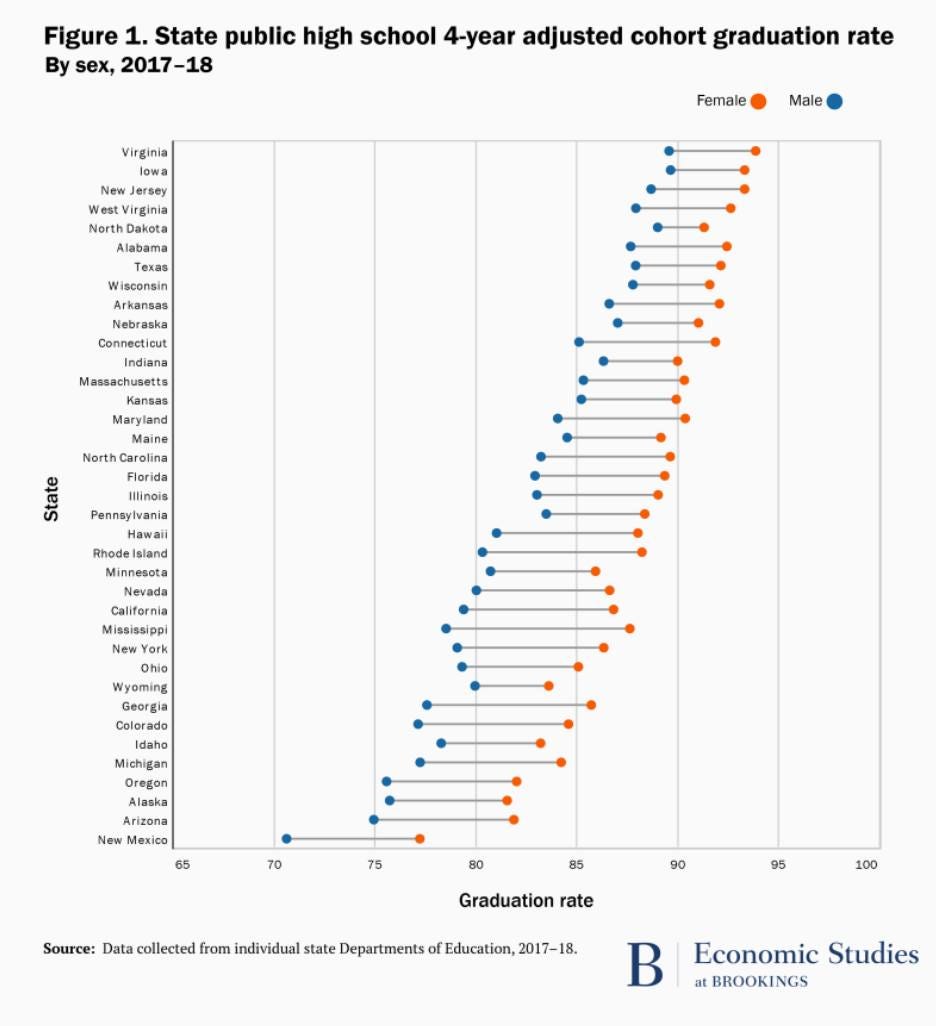

Aside from IQ, there’s the issue of personality. I recently stumbled upon this stat: in every single state in the United States, girls graduate high school within 4 years at a higher rate than boys, and often, it’s not even close.

In the district where I work, 85% of females graduated within 4 years, compared to 74% of males (“advanced” diplomas were 25% female, 16% male). In the district where I currently live, 96% of females graduated within 4 years, compared to 90% of males (“advanced” diplomas were 71% female, 54% male). In the district where I grew up, 96% of females graduated within 4 years, compared to 70% of males (“advanced” diplomas were 30% for both male and female). This is shockingly reliable - but why?

I had a few hypotheses, but after doing a bit of digging, I’m convinced that hereditary differences in male and female personality account for not all, but most, of the gender differences in graduation. Specifically, girls tend to be higher in an aspect of conscientiousness known as orderliness, as well as agreeableness. These differences may not be great on an individual basis, but are significant in the aggregate. The qualities of an orderly person are: likes order, keeps things tidy, follows a schedule, is bothered by messy people, wants everything “just right”, sees that rules are observed, is detail oriented, and is highly organized. The qualities of an agreeable person are: kind, sympathetic, cooperative, warm, and considerate.

We’re venturing into the speculative, but who would you predict would be more successful in school? Someone who is in the 40th percentile of intelligence but 90th percentile in orderliness and agreeableness, versus someone in the 60th percentile of intelligence but the 10th percentile for orderliness and agreeableness? In other words, would the person who is well organized, follows all of the school rules, loves teacher directions in class, and plays well with others, but is of less than average intelligence, get higher grades and be more likely to graduate than the student who is of above average intelligence, but who is disorganized, uninterested in the details of teacher instruction, couldn’t give a damn about the rules, and doesn’t get along with peers and adults? I can easily answer that question. The school system rewards the former over the latter, and the currency is generally grades.

John Hattie wrote a book called Visible Learning. I’m loathe to cite it here, as I believe there are unforgivable methodological errors driving this body of research; however, for those who take him seriously, “Teacher subject matter knowledge” has an effect size of “.11”, or “likely to have small positive impact on student achievement.” In other words, whether or not math teachers know math has almost no effect on student achievement in math, as measured by grades. Take Hattie with a giant grain of salt, but if his finding on this “influence on student achievement” is correct, then the conclusion must be that we are grading students primarily on something other than the subject itself. Which, frankly, does not surprise me. Organized, personable, rule-followers, do better than unorganized, quarrelsome, rebels, almost regardless of intelligence.

Bright kids who are low in orderliness and agreeableness can be annoying, because they often won’t show up to school, they don’t do homework, and they don’t give a shit about your threats, but at the same time, often score relatively high on the standardized tests. What do you do with students who have a 50% average in four quarters of class, but score a 95% or even a 100% on the final exam (in NY, the Regents exam)? I once had an AP student who usually didn’t show up to class, and for the classes she did show up to, slept through the entire lesson. She was one of a mere two of my students to score a “5” (the highest possible score) on the exam. She hadn’t done a single activity, or turned in a single assignment, all year. What do I award her as a grade?

What do you do with the students who fail 9th grade English freshman year, fail 9th grade English again sophomore year while simultaneously passing 10th grade English, and so junior year they are in the weird position of being enrolled in both 9th and 11th grade English? And then, in their junior year, pass 11th grade English but fail 9th grade English yet again!? Do you just acknowledge that if they are passing (theoretically) more rigorous levels of English, then whatever it is that is causing them to fail 9th grade English, it’s not content? Do we just give them the credit at that point? Or do we “hold them accountable” (do we tell them to pick themselves up by their bootstraps)?

The type of teacher who would object to awarding credit to those who aced the exam, but didn’t turn in a single classroom assignment, sees this as a kind of “cheating.” It’s unethical in the same type of way as handing a man a dollar for which he didn’t work. It’s unconscionable…unless you consider that, in this context, students low in orderliness and agreeableness don’t have bootstraps, or boots, or even feet, with which to pick themselves up - at least not in the way the school game is currently played.

There are good reasons for Loren Green’s frustrations. He works very hard to provide engaging learning experiences for students who are largely refusing to participate, or to even show up. I know him personally; he gives many opportunities to students for success. There are also nationwide, post-COVID issues with learning loss and academic standards, and we are all struggling, not only with raising the bar, but figuring out how to raise the bar in a student landscape that is unrecognizable. It’s hard to explain, and I’m not actually sure anyone knows the full extent of what lockdowns have done to students academically, emotionally, and physically.

On the other hand, there are predictable reasons for the decisions that the administrators seem to be making. I argued that school rewards agreeable rule-followers, so it stands to reason that the majority of those who come back to school as teachers were those who found the most comfort in organization, predictability, and compliance; in my experience as a teacher, and as a former aspiring administrator, my opinion is that the administrative ranks are mainly comprised of the most orderly teachers (who are already quite orderly). They are obsessed with goals, schedules, perfection, improvement, and rules. Our attendance and grading policies are in the grips of Goodhart’s Law, which means that the improvement of the metric has taken precedence over what it was the metric was supposed to measure. If administrators can get away with improving attendance by changing the definition of “present” to “in the building for at least ten minutes”, then they are going to do it, because not doing it is going to result in sanctions from the state, and maybe more importantly (to them), the knowledge that they failed in their goal; orderly people can be very judgemental, not only of the students who don't do their homework, but of themselves for not making their graduation or attendance goals. There’s just no way that you can attach high stakes to an unattainable goal, hand that over to a highly orderly person, and expect them not to do everything within their power to game it.

My position for a very long time is that we have to radically diversify pathways to graduation. You can’t have a single game and expect everyone to win. If “graduation requirements” were to do 30 straight pull-ups, a different set of people would win; if it were wilderness survival, a different set; and if it were creative output, a different (and quite narrow) set. There is only one game, so there will only be one set of winners, and there are always going to be a set of losers. In the game that is currently set up, those with a minimum IQ of somewhere around 80, who are also orderly and agreeable, are at an advantage, regardless of bootstraps or grit.

I have recently added to my position that not only do we need to radically diversify pathways to graduation, we also have to radically reassess how we hire, and on this point, I am even less optimistic. There is a particular personality type who do well in school, run teacher training programs, become teachers, and become administrators. I don’t see an easy path to changing that, yet if we diversify graduation requirements and therefore diversify programming, but have the same types of people at the helm, I’m afraid that we’re going to just have the same program in a different wrapper.

Giving something for nothing will create incentives for bad actors to take advantage of systems. Then again, there are some “without bootstraps”, so we are morally obliged to put in place systems to catch them. For what it’s worth, I acknowledge that there will be students who are never going to be successful in school, even if they had all the choice of programming in the world - and if we do set up safety nets for those students, there will always be otherwise capable students who manage to take advantage. It’s a difficult, maybe impossible, balance.

What administrators do or don’t do in their smokey rooms to play their little data games with each other is not the battlefield. Admin are going to admin. The battlefield is codifying into our ed regulations a broad array of games (pathways to graduation) that students can play and win, and diversifying our hires to reflect the best qualities of those diversified pathways.